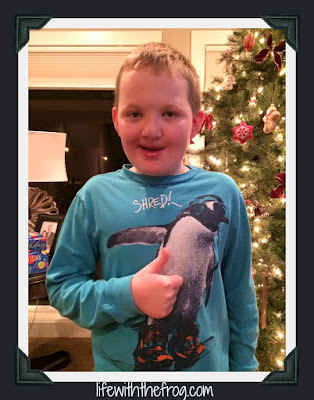

On the drive to school the first day, Slim looked at himself in the rear view mirror and adjusted his new glasses.

"I look good. I really look like I'm in junior high."

I smiled at him and continued to drive through the intersection toward school. In the drop off lane, he bolted out of the car faster than he ever had in the first seven years attending school. I barely had time to say, "Be good, be kind, work hard," my mantra for the last several years.

"I love you! Have a good first day!" I shouted at his back as he bounded down the stairs toward the entrance reserved specially for the seventh and eighth graders.

I honestly never thought I would see this day. This day he made his way through that entrance, wearing the gray polo of a junior high kid instead of the white polo of an elementary kid, actually excited about what lie ahead for him.

We were going to switch him to a different school. Unsure that he could keep up with the rigorous demands of our private school without full-time autism support and without other kids and adults who just "got it."

I prayed for a sign. I prayed for any sign that would indicate he'd be okay if we switched him to the public junior high school.

I should have known, though, that I never get the signs I want.

But I do get the ones I need.

Teachers who "got it," kids who had his back, plans in place, and friends who would move with him to the public high school. All signs pointed to staying put for junior high.

Over the summer I watched him mature before my eyes: taking the dog for walks, making friends in the neighborhood, teaching himself to play golf. I was excited for his teachers to see the maturity, too.

But they never called to meet before school began. And I got worried. I doubted the system. I thought we had to start over from square one.

I held my temper and judgments as I responded to an email. I put a big smile on my face for Open House night. And once again, my fears were quelled.

All six of his teachers were kind. They had heard about him and were versed on the strategies that had been used in sixth grade. The PE teacher and the music teacher already had something set up for him. Everyone had welcoming smiles. My stiff smile became a real one of relief.

It's been four days, and he's already had to visit with the principal about blurting out. I know there are 166 more long days ahead of us, some complete with notes home, or emails, or the dreaded phone call. But we'll make it. You know how I know? We all have three things in common: we care about Slim, we work together, and we have faith in the system.

* * *

Navigating any year in school can be difficult when your child has an IEP or special accommodation plan. As they move up the ladder and have more teachers and more classes, it can get really scary. And as parents, we can get downright tired of all the meetings and phone calls and broken links in the chain. But there are definitely things we can do to make the year go more smoothly for everyone and save headaches down the road.

1. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Don't wait for the teacher(s) to make the first contact. Reach out via an email, letter, or in person. The beginning of the year is crazy busy for teachers and they have so many students and parents to get to know. Let them put names to faces and introduce yourself and your child, as well as tell them something about him.

2. Be patient. It may take a week or so to get plans and behavior charts up and running again. Be sure to check in with the teacher to make sure plans have been put in place.

3. Be supportive at home. For a child who is struggling either academically or behaviorally, home and school plans need to go hand-in-hand. Share with the school what has worked at home, and reinforce both positive and negative consequences from school at home.

4. Find your "person." This is someone who has worked with your child in previous years and knows him well. It could be a special education teacher, a therapist, a PE teacher, or anyone who will work with him year after year. Establish a good relationship and use that person to help in the transition to the next grade. They can share what works and doesn't work with new staff members.

5. Keep an open mind and trust the process. If this year's teacher wants to try something new, hear her out. Most teachers are highly trained and experienced with requirements for continuing education. Maybe a fresh new strategy will work.

6. Have a positive attitude. I know sometimes it can seem like everyone is "out to get" your child or you may feel like they think you're a bad parent; but trust me, they don't. Their job is to help your child while reserving judgement.

7. Know your rights. You know that paper you get every year entitled, "Your rights in special education"? Read it. Learn it. And use it if you have to. Here is a quick and easy to read guide outlining those rights.

8. Chat with other parents of special needs children. You are not in this alone, though it can feel like that sometimes. You can commiserate, share ideas and strategies, and share successes and wins with someone who gets it.

By staying as involved and positive as you can, you are one step closer to ensuring the success and happiness of your special needs student.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter to stay in touch and never miss a post.

Do you have any other advice to add? Share it in the comments or on Facebook. We'd love to hear your wisdom.

And how about all that homework?? Read what parents AND teachers really think about it right here.

1. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Don't wait for the teacher(s) to make the first contact. Reach out via an email, letter, or in person. The beginning of the year is crazy busy for teachers and they have so many students and parents to get to know. Let them put names to faces and introduce yourself and your child, as well as tell them something about him.

2. Be patient. It may take a week or so to get plans and behavior charts up and running again. Be sure to check in with the teacher to make sure plans have been put in place.

3. Be supportive at home. For a child who is struggling either academically or behaviorally, home and school plans need to go hand-in-hand. Share with the school what has worked at home, and reinforce both positive and negative consequences from school at home.

4. Find your "person." This is someone who has worked with your child in previous years and knows him well. It could be a special education teacher, a therapist, a PE teacher, or anyone who will work with him year after year. Establish a good relationship and use that person to help in the transition to the next grade. They can share what works and doesn't work with new staff members.

5. Keep an open mind and trust the process. If this year's teacher wants to try something new, hear her out. Most teachers are highly trained and experienced with requirements for continuing education. Maybe a fresh new strategy will work.

6. Have a positive attitude. I know sometimes it can seem like everyone is "out to get" your child or you may feel like they think you're a bad parent; but trust me, they don't. Their job is to help your child while reserving judgement.

7. Know your rights. You know that paper you get every year entitled, "Your rights in special education"? Read it. Learn it. And use it if you have to. Here is a quick and easy to read guide outlining those rights.

8. Chat with other parents of special needs children. You are not in this alone, though it can feel like that sometimes. You can commiserate, share ideas and strategies, and share successes and wins with someone who gets it.

By staying as involved and positive as you can, you are one step closer to ensuring the success and happiness of your special needs student.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter to stay in touch and never miss a post.

Do you have any other advice to add? Share it in the comments or on Facebook. We'd love to hear your wisdom.

And how about all that homework?? Read what parents AND teachers really think about it right here.